Abstract

Though the wording of this platitude varies slightly when repeated at various judge briefings, it is commonly accepted that the goal of judges in British Parliamentary debate is to emulate the typical, educated, intelligent person. The primary question we are looking at in this study is whether actual BP judges are really doing this. We examine this by comparing the decisions made by normal judging panels at a tournament with decisions made by a panel of educated and intelligent people who have no familiarity with competitive debating. In investigating this question, we come across some other insights about judging as well.

Data Gathering

The HWS Round Robin (“HWS RR” hereafter) is an elite debating competition that invites 16 of the best debate teams and about 16 highly regarded debate judges from around the world each year. To be more precise, of the 16 judges in 2014, when this research was conducted: 13 had broken as a judge at Worlds (the other 3 had never judged at Worlds, but had accomplishments that would no doubt warrant them being invited as subsidized independent adjudicators); 4 had been Worlds grand finalists or had won the ESL championship; 5 had judged in Worlds semis or finals; 1 was top speaker at Worlds; 1 was a Worlds DCA; and 2 were Worlds CAs. Of course, this leaves out countless judging credentials outside of the WUDC. Suffice it to say that this is an exceptionally strong set of judges. The judging pool was 25% female. A total of 6 nationalities were represented.

Over the course of 5 rounds, each team debates every other team exactly once. Judges are allocated such that no judge ever sees the same team more than twice and two judges are never on the same panel more than once.

In 2014, we ran a research study on judging by adding a panel of “lay judges” to each of the preliminary debate rounds. We recruited 40 people who had had no prior experience with competitive public speaking. These lay judges were recruited from faculty, staff and academically high-performing students at HWS. All lay judges were given a very brief (about 30 minute) orientation to judging BP debate, which was as neutral as possible regarding what constituted good debating. (See Appendix A for a summary of what was said at this orientation.) The primary purpose of the orientation was telling them what we were asking them to do and to encourage them to set aside any preconceptions about competitive debating.

The lay judges were assigned to rooms in panels of 3, with 1 person randomly designated as the chair. These people watched their assigned debates silently, as typical audience members would. After the debate was over, they were moved to another room and given 15 minutes to come to a decision about the debate, consulting with no one else. But, before discussing the debate among the panel, they were instructed to write down their initial call on a slip of paper, which we then collected. After the lay judges came to a decision (by consensus or vote), they filled out a ballot indicating team ranks and individual speaker points. In a few cases, there was more than one set of lay judges in the room, and in these cases, they deliberated entirely independently.

The pro judges stayed in the room after the debate and came to a decision, just as a panel ordinarily would. The only difference was that pro judges were also instructed to write down their initial call on paper that was collected.

Almost all of the 20 preliminary debates were video recorded and almost all of the judge deliberations were audio recorded.1 This paper will not discuss any of the information from these recordings, though we hope to engage in some careful qualitative analysis of those recordings in a future publication.

All the quantitative data was entered into a spreadsheet and analyzed using the methods described below. This included:

Pro judge panel ballots (including speaker points)

Lay judge panel ballots (including speaker points)

Individual pro judge initial calls

Individual lay judge initial calls

Methods

A central element of our analysis concerns comparing team rankings provided by individual judges and panels of judges. To do this, we developed a method of measuring the degree of difference between two complete rankings (i.e., ordinal rankings of all four teams). The difference between two complete rankings can be measured on a scale from 0 (representing an identical ranking) to 6 (representing a maximally divergent ranking). A complete ranking can be translated into a set of 6 bilateral rankings, comparing each possible pairing of teams out of the four teams in the room. Each bilateral ranking was scored as a 0 if the two complete rankings agreed on which of those two teams should be ranked higher, and was scored as a 1 if they disagreed. These six scores were then summed to provide the final divergence between the two complete rankings on the 0-6 scale. 2 So, the least divergent rankings (other than full agreement) would be a situation where the rankings are the same, except for two adjacently ranked teams being switched. See the examples below:

We also wanted to measure how similar the initial calls from an entire panel were. To do this, we simply created three pairs of complete rankings from the three judges, calculated the divergence for each of these pairs, and then summed these. This gives a scale from 0 (no disagreement) to 12 (maximum disagreement).3 To make this easier to grasp, consider the table below, where the “call difference” is the degree to which the three judges calls differed.

We used averages of these measures to answer the following questions:

Did pro or lay panels show greater differences in their initial calls?

Did pro or lay judges tend to alter their rankings more to arrive at a final call?

How different were pro and lay panel rankings from each other?

To test for statistical significance of these differences (between A & B), we used a t-test for sample means, controlling for unequal variances:

We tested the following hypothesis to determine the likelihood that the differences were random:

As a point of comparison, we sometimes include what a set of random rankings would look like. To generate this random data for initial call differences between a panel, we numbered all 24 possible rankings for a BP debate, then we used a random number generator in Excel to create three independent random numbers from 1 – 24. We then calculated the call difference of those three rankings and recorded it in a spreadsheet. We did this 100 times and used that sample as our random data for call differences. To get a “random” data distribution for the divergence between just two rankings, we calculated the divergence of the ranking (1,2,3,4) against each of the 24 possible rankings and used that as our “random” distribution. Although not generated randomly, any arbitrarily large set of paired rankings (each randomly selected) would converge on this distribution, so it should more than suffice as a stand in.

Findings & Discussion

Based on our analysis, there are five areas that we want to discuss: 1) the correlation between lay and pro judges regarding team point decisions; 2) the relative similarity between the initial calls of the two kinds of judges; 3) the movement between initial calls and final decisions for the two kinds of judges; 4) situations in which we placed two lay panels in the same room; 5) judge bias toward particular positions in the debate.

Similarity of Final Decisions

The data clearly shows that there is a correlation between the winners chosen by the lay judges to those chosen by the pro judges. It would have been both horribly depressing and a damning indictment of our activity if this had not been the case.

At the same time, we want to note that the break would have looked very different if the lay judges had been deciding the winners. The top breaking team would not have changed and the second team would have squeaked in as 4th seed (on a tie-breaker), but the other two teams who broke to finals would have been 8th and 9th on the tab. What stands out to us in the comparison of the results from lay vs. pro judges is that there were 3 teams whose total team points from the two groups differed by 5 or 6 over just five rounds. An additional 4 teams had results differing by 3 or 4 team points. Putting this another way, there were 2 teams that the pro judges liked much more than the lay judges (5 points), and there were 3 teams that the lay judges liked much more than the pro judges (4-6 points). The average difference for a team at the end of five rounds was 2.625, which is substantial, since the average point total is 7.5. The chart below shows the different results from the two sets of judges. Team names were alphabetized to show the order in which they would have finished by the lay judges’ rankings (i.e., “Team A” would have broken first, “Team B” second, “Team C” third, etc.).

Although there is a correlation between the two sets of results, there are some significant aberrations. In fact, the differences between the two sets of results are greater than the chart above suggests, since the data presented in the chart above only considers the teams’ final score, not the accumulated variance in the decisions from each rounds.4 So, the chart below may better represent the amount of disagreement between lay and pro judges. What is striking here is that even in cases where there appeared to be strong agreement on the results (e.g., teams A, E, G and L), the reasons for that result were very different, varying by 4-6 points in these four cases. Though we did not represent it in the chart below, the expected accumulated differences between any set of team rankings and a random set of rankings is 6.25 for each team over five rounds. So, they two sets of judges are coordinating better than random, but that’s not a high bar.

Clearly, the pro and lay panels saw some debates very differently, and the quantitative data that we have will not answer the question of why this is the case. Our intention is to move forward with this research by engaging in a qualitative analysis of the audiotapes that we have of the deliberations of pro and lay panels, particularly in the rounds where they disagreed markedly.

While the accumulated differences shown above make it seem as though the decisions by the lay and pro panels were quite substantial, things look somewhat different when we view the data in a different way. We calculated the divergence between the rankings of the pro and lay panels in each round and found the distribution of these. For comparison, we added what a distribution of divergences from random rankings would look like and we also added the distribution of divergences from individual pro judges on the same panel at this tournament.

There is only the smallest possible divergence or no divergence at all between the lay and pro panels in 44% of all cases. In another 28% of cases, there was a divergence of 2, which we still consider a fairly similar ranking. Although a divergence of 3 or 4 is definitely substantial, it is important to note that there were no cases where the calls of the two panels diverged as much as 5 or 6. The lay panels diverged from the pro panels slightly less than the individual pro judges on the same panel diverged from each other.5 This suggests that there is not such a big difference between how pro and lay judges see the debates.

Similarity of Initial Calls

Regarding the differences in the initial calls of the judging panels, the data reflected what we expected to see, but not to the degree that we expected. Pro judge panels tended to be more consistent (i.e., less divergent) than lay judge panels. However, there was a greater average difference than we had expected between the initial calls of the pro judge panels. In other words, we expected the pro judges to agree even more before the panel discussion began.

In the 20 prelim rooms, there was never a case where the pros completely agreed, though perhaps that isn’t quite as remarkable once you consider that the odds of this agreement randomly happening are 1 in 576. In 47% of the rounds the pro panel’s call difference was minimal, meaning that it was either 2 (the smallest possible difference, outside of complete agreement) or 4 (the next smallest). We see these differences as relatively minor, and indicative of a panel being largely on the same page at the end of the debate. These are situations that would likely set the stage for a fairly easy deliberation. We consider call differences of 6 to be moderately divergent. Although panels with call difference of 6 will find it somewhat more difficult to reach consensus, there will be some clear commonalities in the three judges’ rankings that can help to find a path to consensus. About 24% of pro panels fell into this range. We consider panels with a call difference of 8 (12% of pro panels) to be significantly divergent. These panels will likely struggle to find commonalities in their rankings, though some will likely exist. We consider call differences of 10 or 12 to be extreme, since these calls indicate virtually no agreement. In 18% of pro panels, there were such extreme differences. We feel sorry for the people engaged in these deliberations. Of course, we acknowledge that in some cases, these extreme call differences can dissipate quickly once the panel resolves one or two central questions about the debate. But, many times this is not what happens.

In contrast, the lay judges had minimal or no call difference (0-4) in 28% of their panels, many fewer than the pro panels. About 32% of lay panels had a moderately divergent call difference of 6. About 12% of lay panels had a significantly divergent call difference of 8. The remaining 28% of panels had extremely divergent call differences.

We note that even with panels of uniformly excellent judges, about 30% of panels will disagree to a significant or extreme degree in their initial impression about who won a debate. This fact strongly suggests that even the most confident judge among us should cultivate a sense of humility regarding their call in a debate. This is even clearer for those people considering criticizing a decision without participating in the deliberation process.

The average call difference for lay panels was 6.5, with a standard deviation of 3.38. This compares to an average of 5.9 for pro panels, with a standard deviation of 2.87. An average random set of three rankings had a call difference of 8.9, with a standard deviation of 2.67. We had expected that pro judges would have a certain uniformity of expectations and criteria and that this would result in more uniformity in their initial call. While our findings were not strictly inconsistent with this, as mentioned above, we had expected to find a larger gap between the pro and lay panels in this respect. The gap we found was not even statistically significant.6

The size of these call differences suggests that all judges should remember that the panel deliberation is a essential element in coming to a good decision and that judges (chairs in particular) should not see their job in the deliberation as ensuring that the other judges are willing to go along with their initial call.

Movement from Initial Calls to Final Decisions

We use the term “movement” to refer to how much a judge’s initial call diverges from their panel’s final call. When there is an initial call difference among the judges on a panel, there will necessarily be some movement by some of the judges. But panels will not always come to a final decision that minimizes how much the judges move. For better or worse, in practice, panels sometimes engage in deliberations that cause everyone on the panel to change their mind about a ranking that they had all agreed on. So, the existence of an initial call difference sets a minimum amount of movement that needs to happen to reach consensus, but judge movement can significantly exceed this. In theory, a panel could start with complete agreement (i.e., no call difference) and end with a call that is completely different from what everyone initially thought. So, movement measures something new.

Given that pro judge panels had a lower call difference on average, one might reasonably expect that the pro judges would tend to move less than the lay judges. However, the data showed that the lay judges moved an average of 1.3 between their initial call and their final judgment, with a standard deviation of 1.41. The pro judges moved an average of 1.8 between their initial call and their final judgment, with a standard deviation of 1.43. This difference of .5 is both statistically significant and potentially revealing.7 One might try to explain the fact that lay judges moved less than pro judges, by focusing on the 2 lay panels that agreed immediately, but this only accounts for 6 of the 27 instances of 0 movement. Moreover, these 2 panels with 0 call difference equally affected the call difference average, and so cannot really explain the fact that lay judges moved less even though they started by disagreeing more.

The chart shows that lay judges most frequently do not move at all from their initial call, and their tendency to move tappers fairly steadily as the divergence increases. In contrast, the pro judges were about equally likely to move 0, 1, 2 or 3 degrees to the final panel decision, but the likelihood that they would move more than 3 drops precipitously. It is unclear if this precipitous drop is just a statistical aberration based on our small sample size or if there is a real cause to why pro judges are dramatically less likely to move beyond 3 degrees of divergence.

One possible explanation of why the lay judges had a smaller average movement despite starting further apart is that lay judges were more conciliatory and attempted to minimize the degree to which the panel members needed to move by being willing to compromise (i.e., split the difference). This is only one possible hypothesis and we make no judgment about whether a conciliatory attitude is beneficial to judging or not. It is possible that discussions among the pro judges revealed deeper insights into the debate that caused many people on the panel to reevaluate their initial calls. It is also possible that pro judges attempted to do this, but actually just ended up distracting themselves from their more accurate first impressions. Perhaps our future qualitative analysis of the deliberation recordings will shed some light on this.

Do distinct lay panels come to similar conclusions?

As we said above, at the start of this research we anticipated finding that pro judges were more internally consistent (less divergent) in their rankings, both as individuals and as panels. The analysis of call differences suggests that as individuals, pro judges are more consistent with each other than lay judges are. However, we have no direct evidence about the extent to which different pro panels would be consistent. Our data did provide us with some modest evidence about consistency between lay panels because we had enough volunteer lay judges during some rounds to put two lay panels in the same room. We were able to do this five times and the results seem worth reporting.

There was a high degree of consistency between the two lay panels in these five rooms. In two rooms, they were in perfect agreement. In two others, they had the smallest degree of divergence and in the final room, they diverged by 2 still were largely in agreement. So, the average divergence between 2 lay panels was 0.8. In contrast, the average divergence between these panels and the pro panels that were in their respective rooms was 1.4. The sample size is too small to determine statistical significance, but it seemed to us that it was worth remarking on.

Judging bias towards debating positions

We looked at the data on how well the various team and speaker positions did according to the points that the two sets of judges awarded them. The clear trends in the data are:

Closing opposition teams were likely to do better with both pro and lay judges

Opening government teams were likely to do worse with both pro and lay judges

These biases were more pronounced with the lay judges, especially the preference for closing opposition teams.8

To provide a frame of reference, we compare our data from the 2014 HWS RR with data from the past seven years of the HWS RR, and also with the data from the 2014 WUDC in Chennai. We compared these by adding up all the points won by teams in each position during the preliminary rounds of these tournaments and then calculating the percentage of the total points that this represented.

The result was both interesting and remarkably boring. The results are boring because all of these sets of judges award points in basically the same zigzag pattern. But, the results are interesting partly because there is this consistency, and particularly because the lay judges not only replicated this pattern, but did so in an exaggerated manner. This strongly suggests that the bias in favor of opposition teams (and against the opening government team) is not a function of some set of habits or expectations developed within our debating community, but rather is an outgrowth of something about how the nature of those positions relates to an audience.

As a final note, we hope that this short publication will spark discussion about these issues and will also prompt people to suggest new ways for us to analyze the data that we have at our disposal.

Limitations & Directions for Future Research

There were several limitations on our research.

Obviously, with only 20 preliminary rounds, the data set we are working with is a fairly small sample size.

Because the HWS RR has such an unusually high caliber of debaters and judges, one might question the extent to which we can generalize to more typical debates.

Because the HWS RR uses team codes, the debaters schools were anonymous with lay judges (who were also unaware of particular debater reputations), but most of the judges were likely aware of who all (or almost all) of the debaters were.

A small amount of our data needed to be discarded because forms were incomplete or not filled out correctly (e.g., a judge would fill out the initial call sheet without giving each of the four teams a unique rank from 1-4).

There were no rooms with more than one pro judging panel, so we are unable to determine the consistency between pro panel decisions after deliberation.

As mentioned above, we plan to pursue further qualitative research based on the audio recordings made at the 2014 HWS RR. This will hopefully provide a significantly more textured and nuanced view of what was happening within the deliberations of panels with the two kinds of judges.

Conducting this research again at the HWS RR or at other tournaments could increase the sample size. Additionally, it would be fascinating to gather more data on the consistency of pro panels. On possibility would be to hold a (presumably small) tournament where each room had two pro panels. Teams would simply accumulate points from both panels. This would be very simple to do in a round robin format, but would also be possible in more traditional formats, though it would need to be hand tabulated (or software would need to be developed). Such a tournament could provide a wealth of useful data about how consistent judging panels are.

Appendix A: Instructions to Lay Judges

The handout below was given to all volunteer lay judges along with an explanation of each point on the handout. Volunteers had an opportunity to ask questions as well. All volunteers were screened to ensure that they had had no previous exposure to any form of competitive debating.

HWS Debate Research

Before you start:

– Please set aside everything you think you know about what competitive debate should be like.

– We are interested in your perspective as an intelligent and thoughtful listener.

– It is not easy, but please do all you can to set aside your own personal biases and beliefs.

– Try to forget whether you actually agree with one side or the other.

– Try to forget any particular pet theories that you tend to favor.

– Try to adopt what you take to be the bland beliefs of a typical, intelligent, educated person.

– If an ordinary, intelligent, educated person would accept or reject a claim, you should too, regardless of whether other debaters refute it.

– Ask yourself: Who would have persuaded me most if I really were an unbiased person?

This is a contest of who is best at rational persuasion, not a contest of who presents the most eloquent speech. Obviously, good speaking style helps one persuade an audience, but we are asking you to judge what would actually persuade a rational, intelligent and educated audience. This is a holistic judgment that is not exclusively about style or content. The question is “Who was most persuasive?” and we offer no formula for coming to that decision.

Things you must know:

– There are 4 teams competing in each debate.

– The 2 teams on the left are supporting the plan or proposition stated by the first speaker.

– The 2 teams on the right are opposing this plan or proposition.

– But, judges do not declare either “side” of the debate (i.e., either “bench”) the winning side.

– Rank them “Best”, “Second”, “Third” and “Fourth” based on how persuasive they were.

– Which team, considered as a whole, was most likely to ACTUALLY persuade an unbiased, intelligent and well-educated audience.

– Before your panel begins its discussion, please take just one or two minutes to write down the ranking of the teams that you (on your own) think is most appropriate. But, after this, please be willing to revise this ranking if the discussion actually makes you see things differently.

– Judging a debate is a COOPERATIVE exercise. DO NOT VIEW THIS AS A COMPETITION to convince the others that your initial impression is correct. The goal is to work together to find the best answer to the question of which team was more persuasive of an intelligent, educated and unbiased audience.

– After coming to a decision on the team rankings, we ask that your panel assign points to each individual debater on a scale of 50 (poor) – 100 (excellent). These points should reflect the speaker’s overall contribution to persuading an intelligent, educated and unbiased audience that their side is correct.

– So, this includes quality of argumentation and quality of style.

– The average points at this tournament are typically about 79.

Things you should know:

– One person in each panel of 3 judges has been assigned to be the “chair”, which means only that they keep an eye on the time and try to ensure that the deliberation moves along so that your panel is ready to render a decision at the end of 15 minutes about how all 4 teams ranked.

– The 2 teams on the same side need to (largely) agree with each other.

– Disagreeing with a team on the same side is called “knifing”.

– This is to be considered a negative exactly to the degree that it undermines the overall persuasiveness of their side’s position. (So, a small disagreement about an unimportant element can be mostly ignored.)

– The debate is about the main proposition articulated by the first speaker, which may be somewhat more specific that the general ‘motion’ (i.e., topic) announced before the debate. Focus on the proposition, not the motion.

– You are permitted to take notes, but you are not required to do so.

Things you might want to know:

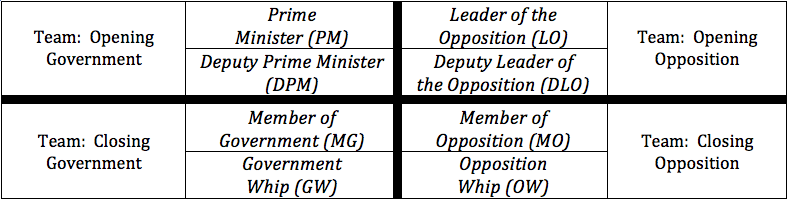

This is a guide to some unfamiliar terminology that might be used in the debate. Below are the names of the various teams (in the outside columns) and names of the individual speaking positions (in the inside columns):

– During the middle 5 minutes of a speaker’s 7 minute speech, debaters on the other side can stand up for a point of information (POI). The speaker can either accept or turn down these POIs, but typically they are expected to accept 2 during each speech. The perception is that failing to do this demonstrates a lack of confidence.

There were some technical difficulties that prevented recording in some of the debates.

In other words, for any two ordinal rankings of four teams in a room (e.g., CG/OG/CO/OO and OG/CG/OO/CO), we asked the following six questions: Did they agree on whether OG placed above OO?; Did they agree on whether OG placed above CG?; Did they agree on whether OG placed above CO?; Did they agree on whether OO placed above CG?; Did they agree on whether OO placed above CO?; Did they agree on whether CG placed above CO? Using the example just given, the answers would be: yes, no, yes, yes, no, yes.

Answers of “yes” were represented with a 0, while answers of “no” were represented by a 1. So, in the same example, the answers were represented as (0,1,0,0,1,0). The sum of these represents the divergence between two rankings. So, in this example, these rankings diverge by 2 degrees out of a possible 6.

Only even numbers are possible on this scale, but we chose not to simplify it to a 6 points scale in order to make it more obvious when we were talking about comparing panel rankings, as opposed to bilateral comparisons between rankings.

In each round, the difference between the team points given to particular team by the pro judges and the lay judges will be somewhere between +3 and -3. The “accumulated variances” for a team is the sum of the absolute values of all individual divergences in the five prelim rounds. The “final difference” is the sum of these values (not the absolute values). So, for example, imagine that a team got the same points from the pro and lay judges in the first three rounds, then in round four got ranked 1 point higher by the lay judges than by the pro judges, and then in round five got ranked 2 points lower by the lay judges than by the pros. That team would have a final difference of 1, but an accumulated difference of 3.

Comparing the lay and pro panel divergence to the divergence between individual pro judge rankings and their pro panel rankings would not be useful, because those are not causally independent rankings. Below, we do discuss the distinct issue of how much judge rankings move from their initial call to the final panel ranking.

The t-statistic for the test on this data turned out to be 0.6124. Given this statistic, we fail to reject the null hypothesis that the average difference in initial rankings for lay judges and debate judges are equal.

The t-value = 3.33, significant at a 99% confidence level (i.e., a significance level of 0.01), found by t-test for sample means controlling for unequal variances. Given this statistic, we do reject the null hypothesis that the average movement for lay judges and debate judges are equal.

We are not using the word “bias” in a pejorative sense. We mean it merely in the statistical sense.